PHILADELPHIA

Here After: Megan Biddle and Erin Woodbrey

Feb 18 – Apr 1, 2023

Opening Reception: Thu, Mar 9, 6 - 9 pm

Expand to read the essay by by Leah Triplett Harrington

-

by Leah Triplett Harrington

“…but we have not heard about the thing to put things in, the container for the thing contained. That is a new story. That is news.

And yet old.”

–Ursula K LeGuin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986

Do you know how fossils are formed? Yes, a being dies, or a thing is no longer of use; the being or thing goes into the ground to later be found as a mere trace, a fragment, a particle fused with the earth. Actually, there are a few ways that fossils are formed, artist Megan Biddle tells me. We are talking about Here After, Biddle’s two-person show with Erin Woodbrey, which presents sculptures and prints that deal with time and its transformation of materials, beings, and things.

For Biddle and Woodbrey, who work between two and three dimensions (installation, sculpture, printmaking), time and its relationship to our bodies and things is a constant theme, no matter the media. Both deeply process-based, they each consider how materials interact with their environments, examining how naturally-sourced yet human-manipulated substances evolve with time. For Biddle, glass and its making is a material and process allowing for the study of cycles of time, its manifestation in physical form, and how they hold narratives. And for Woodbrey, concrete-looking ash encasements are a poetic means for projecting a future for our physical selves and stuff. I see fossilization as an aesthetic approach and conceptual pursuit in both of their practices.

Encasing, casting, compressing: these are ways in which to contain or hold something. So back to our conversation, to understand how fossils are made, we must consider the container. Ursula K. LeGuin’s stunning but short essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” is a lucid lens through which to understand material containing and to imagine fossilization as an aesthetic for Biddle and Woodbrey. In the essay, LeGuin suggests that the true hero of human civilization and its attending cultures is a humble bag with which people began carrying food and other means of survival. She describes a story’s ideal form as a sack. “A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us,” LeGuin writes. This idea is at once ancient and radical.

The exchange between Biddle and Woodbrey is new–the two met over the summer of 2022 while Biddle had a show at Farm Projects–but nevertheless seems old, recent but well-established. In Here After, the pair meditates on time eroding the present into the past, and what will happen here when now is an after. Their formal and conceptual relationships contrast and complement each other, expanding into a dialogue on the tension between presence and decay.

Seemingly caught in stasis between construction and disintegration, Woodbrey’s assembled sculptures use time and space as media. “The Carrier Bag Series,” inspired by LeGuin’s essay, gathers nodes of grey shapes–not quite abstract, not totally representational, more suggestive–onto wire garden plant supports. The shapes are sourced from Woodbrey’s vast collection of discarded single-use containers (metals, foam, paper, and plastics), which archives her own use of such containers and objects. Taking her emptied, would-be discarded plastic, she covers it in ash from her own studio or gathered from grills, campfires, and fireplaces of friends and neighbors, hastening a fossilization process of sorts. These shapes are by-products of human material use over time and are contoured by the plant supports (itself a means for humans to shape nature). Delicately arranged and spread into patterns of precarity along the wire supports, they evoke the fragile tenuousness of our relationship with environmental ecologies. Sometimes presented singularly or sometimes as an assemblage of sculptures installed along a plywood and cinder-block plinth, “The Carrier Bag Series” figures as a liminal display of our future fossils.

As with Woodbrey’s installations, Biddle’s glass-casting sculptures make use of their innate precarity to suggest the future of today’s ephemera. And while Woodbrey encases to preserve, Biddle fills to capture and contain. In “Future Relics,” Biddle uses a sand cast process to build lava-like layers of globby black glass, arranged into wall-hanging groups as if bits of thick roots were spread across a wall. Here, Biddle makes use of a sand mold, a container, creating a form from an emptiness filled with natural material. As their title implies, “Future Relics” traces a presence to forecast its artifact, while “Drift and Drag” suggests how our stuff circulates and then settles into obsolesce. In the latter, pipe-like cylinders of lustrous purple-ish lavender extrude from the wall, each created through an extraction process in which clay is pushed through the extruder, glass eventually filling the empty cavity. The cylindrical shapes stacked atop each other in an uneven row, “Drift and Drag” varies in color from dark to almost pearly purple and is the culmination of experimentation with color and opacity for Biddle. Allowing the material and its inborn chemical reactions to dictate its own form and shape, Biddle is “freer” this way, trusting the materials she’s intimate with to inform the objects they will become.

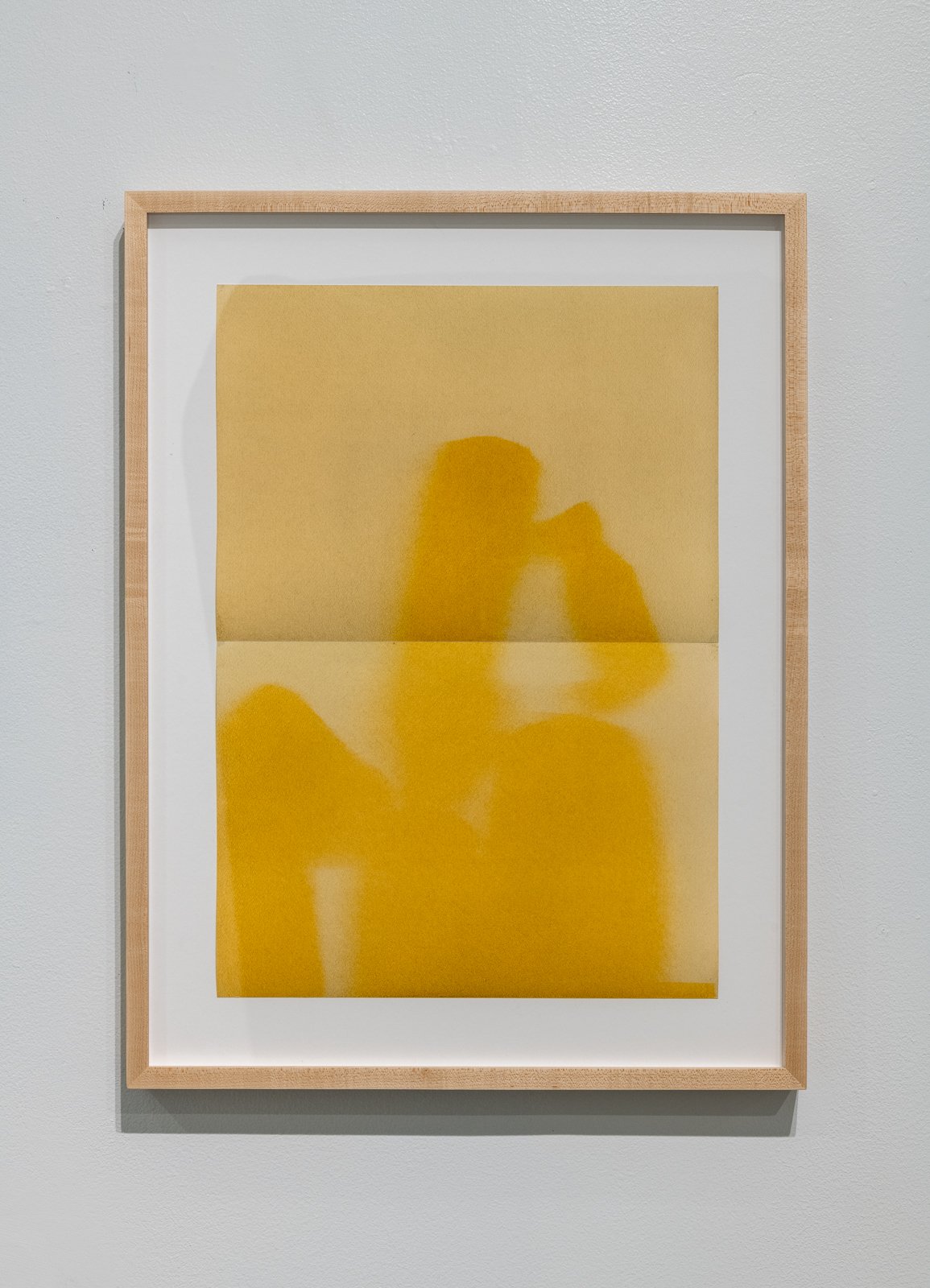

Looking simultaneously forward and back are Biddle and Woodbrey’s 2D works, in “Here After” monotypes and anthotypes, respectively. Both image-making techniques laboriously produce single images from a composition; monotypes replicate an image into another, while anthotypes are created through cast shadows and sunlight via plant-based emulsions and physical objects. Like their sculpture, Biddle and Woodbrey’s printed works create records and are confluences of interactions between time, material, and objects. Somehow Biddle and Woodbrey are hazily assertive in these prints, their lines more distinct, their colors more saturated–their forms more figurative. Still, these prints elide easy or specific categorization; they are stylistically and formally hazy, especially at the edges. Between Woodbrey’s shadowy oblong bottles and circles, blues and oranges fade into light; Biddle’s short rake-ish lines bleed into one another, creating scale-like patterns. These prints are, therefore, at a precipice of transformation. One image becomes another. One moment passes into an after.

So I don’t know how fossils are formed, to return to my conversation with Biddle and Woodbrey. But tracing their works for Here After, I start to guess. Fossils look forward and backward simultaneously. Fossils contain stories, records, and are unwitting archives. Fossils accumulate over years and years of process. Fossils are old and new at the same time, always evolving (perhaps until someone encases them in a museum). And in Here After, Biddle and Woodbrey suppose some fossils for now and for the after, pondering how they might be formed in the future.

Leah Triplett Harrington is a curator, writer, and editor. As curator for Now + There, she facilitates the Public Art Accelerator and organizes large-scale public art commissions. She is also editor-at-large for Boston Art Review. Her writing has most recently appeared in that publication and ArtNet News, Sculpture, Public Art Dialogue, Flash Art, Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, and others. As an independent curator, she has organized projects for Boston University Art Galleries, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, Trestle Gallery, Herter Gallery, and others. In 2021, she was the inaugural curatorial mentor for Praise Shadows Art Gallery and taught in the MFA program in Painting at Boston University.

Tiger Strikes Asteroid Philadelphia (TSA PHL) is pleased to present Here After, a two-person exhibition featuring the work of Megan Biddle and Erin Woodbrey. Working across two and three dimensions, the work in Here After toggles between registers of time and physicality. What seems to be in a state of fluidity and movement is, in fact, in stasis. What is heavy is light, and that which is new seems from another time. Through objects made by naturally-occurring and fabricated processes and materials, both artists examine a spectrum of states between permanence and decay. The exhibition will be accompanied with “The Old, the New, the Fossil: Megan Biddle and Erin Woodbrey’s Here After,“ an essay by Leah Triplett Harrington.

Ripples of glass are fossilized like scars in one of Biddle’s relief sculptures entitled Future Relics. The title references a memorial object of a time we have not yet encountered, impressing upon the material world like wounds from a pressure ulcer. The dark black glass of these works is encrusted with sand, residue from their making. To produce these sculptures, Biddle plunges an object into a bed of sand, as if to explore the unseen terrain below. The resulting hollow is filled with molten black glass. This process echoes the tension between surface and what lies beneath, a theme which reverberates throughout her work.

In Woodbrey’s The Carrier Bag Series, an ongoing body of sculptural and related photographic works, objects are illuminated and entombed in a mixture of ash, plaster, and gauze. As if pulled from a museum of a future past, these free-standing sculptures reference both contemporary and ancient objects, building materials, and analog forms. The series draws its title from Ursula K. Le Guin’s radical rethinking of the story of human origin and technology in "The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” Catalyzed by this and the urgency to rethink materials and cycles of waste and consumption, Woodbrey examines the paradox built into objects that are intended to be discarded but not intended to decompose. Through a careful repurposing of material, the container is animated from within, becoming a central figure in a narrative about accumulation and new materiality.

Megan Biddle has attended residencies at Macdowell, The Jentel Foundation, The Creative Glass Center of America, Sculpture Space, The Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Pilchuck Glass School, Northlands Creative Glass in Scotland, Haystack Mountain School of Crafts and Mass MOCA. She has exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including A.I.R Gallery, Brooklyn, The Islip Art Museum and the Everson Art Museum in New York; the Reynolds Gallery Richmond, VA.; Space 1026 and Philadelphia Art Alliance in Philadelphia, PA.; Galerie VSUP in the Czech Republic; and the 700IS Experimental Film Festival in Iceland, and Shau Fenster and NationalMuseum in Berlin, Germany. Her work was acquired into the American Embassy’s permanent collection in Riga, Latvia. She has taught at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Pilchuck Glass School, Urban Glass, Oxbow School of Art and currently teaches as an adjunct professor in the Glass Program at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture. She is a member of Tiger Strikes Asteroid, Philadelphia where she lives.

Erin Woodbrey’s recent solo and two-person exhibitions include of the Sun, Yes We Cannibal, Baton Rouge, LA; Wilder Alison + Erin Woodbrey, Gaa Gallery, Expo Chicago, Chicago, IL; Beacon, 201 Telephone Box Gallery, St. Andrews, Scotland; The Fragment Series, Gaa Gallery, Provincetown, MA; Quill Isn’t Staying Now, with Dani ReStack, Gaa Projects, Cologne, Germany; Leg, Limber, Lumber, Limb, Higgins Gallery, Barnstable, MA; Time Mothers, Gaa Gallery, Provincetown, MA; and Material Studies, Arena Gallery, Liverpool, UK. Woodbrey’s work has been included group exhibitions at White Columns (Online), New York, NY; SPACE, Portland, ME; Cry Baby, Berlin, Germany; Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, ME; SÍM Gallery, Reykjavík, Iceland; Greylight Projects, Hoensbroek, Netherlands USA; USA; International Print Center, New York, NY, and Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, Estonia, among others. Woodbrey received an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2014. In 2007 she completed a BFA at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, where she also is the recipient of a 2017-18 Traveling Fellowship.

Leah Triplett Harrington is a curator, writer, and editor. As curator for Now + There, she facilitates the Public Art Accelerator and organizes large-scale public art commissions. She is also editor-at-large for Boston Art Review. Her writing has most recently appeared in that publication and ArtNet News, Sculpture, Public Art Dialogue, Flash Art, Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, and others. As an independent curator, she has organized projects for Boston University Art Galleries, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, Trestle Gallery, Herter Gallery, and others. In 2021, she was the inaugural curatorial mentor for Praise Shadows Art Gallery and taught in the MFA program in Painting at Boston University.

photos by Constance Mensh